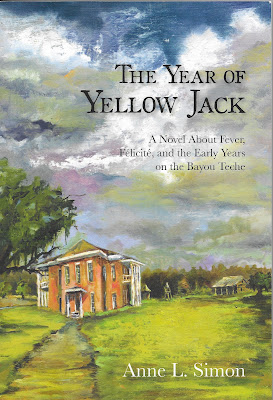

Anne L. Simon has “found her oeuvre” in historical fiction. Her recent novel, The Year of Yellow Jack, is a fascinating story about New Iberia, Louisiana — the successes and tragedies of families living in this south Louisiana town of Bayou Teche country during the 19th century.

The Year of Yellow Jack emerges as a regional story with a universal message and is the result of Simon’s meticulous research and lively imagination. Simon’s story is told in realistic voice about a social system that prevailed during this antebellum period in southern history and includes both wealthy and enslaved characters — the Bérard and Duperier families and their antecedents, and a Haitian woman of color named Félicité.

Both the “Foreword” and “Historical Notes” in this volume indicate the depth of research and dedication to an intriguing project Simon pursued for three years and provide a sampling of her accomplished expository style. The novel is narrated in three parts and covers the multicultural mix of south Louisiana — French, Spanish, African, English, and Attakapas who settled the towns of New Iberia and St. Martinville. In this mix, Henri Frederick Duperier and Hortense Bérard emerge as major characters who marry and build a home on the banks of Bayou Teche and are joined by Félicité, the enslaved woman of color from Saint-Domingue.

Simon’s research of colonial New Iberia and St. Martinville, Louisiana includes descriptions of the prevailing attitudes toward the enslaved during the early 1800s; e.g.,the rumination of Hortense Duperier: “When I was a small child, we had many slaves in our household. Patterning my behavior on that of my mother, I expected the slaves to do without question whatever they were asked to do, even when asked by a child. I could not recall any open discussion of their inferior status. Occasionally Maman corrected my behavior. She instructed me to be courteous at all times, not out of respect for the role the slaves played in our lives, but because courtesy was expected of people of privilege. I accepted the world I had been born into as normal. I gave little thought to the personal lives of those who lived behind the woods that separated us from them…”

Simon’s descriptions of Teche country landscape during the 19th century are succinct and skillfully done through the device of dialogue; e.g., Grandpa Bérard’s : “It was springtime in Teche country, and beautiful. The Garden of Eden, we thought. Untouched forests, not like the worn-out land we’d left behind in France. Oak, willow, and cottonwoods lined the bayous, giant cypress and tupelo trees thrived in the wetlands. Natural meadows spread to the west…”

The major event that tied families of privilege in New Iberia and St. Martinville and the enslaved Félicité occurs in Part III of this novel when Félicité functions as a healer during the siege of yellow fever that strikes these communities. Using non-traditional medicine in the forms of hydration and herbs (fever tea), Félicité saves many lives and helps to "wash clean New Town (New Iberia)" of this deadly disease.

Interspersed in this narrative about Hortense Duperier and Félicité is a salute to Frederick Duperier — his valuable part in incorporating the town of New Iberia. The relationship of early settlers and the Atakapa Isak Nation, or the Attakapas are also included — facts corroborated by Simon through a record in the St. Martin Parish courthouse that shows Bernard, chief of the Atakapas, granting land to Hortense Duperier’s Grandfather Bérard Such discoveries indicate Simon’s investigative abilities as well as her persistence in ferreting out facts that enhance the narrative.

Scholarship and vision intertwine throughout this intriguing novel. Photographs included in The Year of Yellow Jack indicate the close relationship that Félicité had with the Duperier family of New Iberia — one of them features the Duperier family plot that shows Félicité’s grave marker as she is buried alongside her appreciative and respectful family.

The Year of Yellow Jack will intrigue south Louisiana residents, but its range is far-reaching in that it corroborates a major contribution made by an enslaved Haitian woman during the colonial period of American history. It also shows the bravado and competence of a widow who overcomes financial reverses and takes her place in history as an enlightened woman who refuses to be deterred by social mores. As I said, Simon has found her oeuvre in historical fiction, and The Year of Yellow Jack celebrates her place in this genre. Just as we celebrate Anne’s contribution — Brava, Anne!

Anne L.Simon was educated at Wellesley College, Yale, and LSU Law School. She was elected as a general jurisdiction trial court judge, and after mandatory retirement served in ad hoc and pro tempore appointments by the Louisiana Supreme Court, as an Appellate Court Judge for three Indian tribes in Louisiana, and was the Louisiana Court Improvement Fellow for the Pelican Center for Children and Families. She has authored three crime novels, entitled Blood in the Cane Field, Blood in the Lake, and Blood of the Believers "loosely based on her experiences."

Published by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press.

Note: I am familiar with stories about the scourge of yellow fever through the Anglican Sisters of the Community of St. Mary at Sewanee who, every year, relate the legend of “The Martyrs of Memphis,” the story of Anglican Sisters who nursed yellow fever victims in Memphis, Tennessee during the siege of 1878. I was drawn to Simon’s story because of historical similarities. However, my initial interest in Félicité began with a strange telephone call from a psychic named John Russel in San Angelo, Texas who called me one evening during the 1980s and asked if I knew why he was receiving psychic messages including my name and someone named Felicity in New Iberia. I told him I didn’t know anyone named Felicity, but I later remembered the marker honoring Félicité’s work with yellow fever located near the New Iberia Library. I never heard from this caller again. However, he had piqued my interest in the enslaved healer, and, later, I included Félicité as a character in a young adult novel entitled Flood on the Rio Teche that was more imagination and less factual than Anne Simon’s meticulously researched work of historical fiction.

No comments:

Post a Comment